Wachiye! Ntishinakason nipi.

Hello! My name is water (Alyssa) and I am a Cree student midwife. As I sit here breastfeeding my new baby, I reflect upon the fact that I had Siikwan (Spring in Cree) in my womb while I completed a two-month mifwifery placement in Attawapiskat, a remote fly‑in community located near the west coast of the James Bay.

Going to Attawapiskat was truly life‑changing in that it confirmed my desire to practice midwifery in rural/remote northern Ontario. And when I say north, I mean, north of North Bay! While I was there, I worked within the Attawapiskat Health Centre where Neepeeshowan Midwives is housed. I built inter-professional relationships with other health care providers, attended training sessions, held prenatal classes with a community member who became a friend of mine, and enjoyed walks by the Attawapiskat river with the founding midwife’s dog. Not to mention, the cute seals who made an appearance more than once.

If you live in Canada, you probably saw a lot of media coverage on Attawapiskat in recent years. Although some of it is true, we must remember that the media can really misrepresent Indigenous communities. It is true that communities are still healing from colonization, the wrath of residential schooling and consequent effects, but there is such beauty in how resilient we are. One of the ways in which Indigenous communities are taking back their traditional practices is in the craft and strength of Indigenous midwives.

As a Cree person, my true healing began with midwifery and there was something so incredibly powerful in being on the land and gaining more experience in a remote context while growing part of a future generation inside of me. When I traveled to Attawapiskat, I was in my second trimester of pregnancy. As I sat on the plane, I was reminded of the reality that childbearing people in remote communities must face when they get pregnant. While midwives support choice of birthplace, confinement and flying outside of the community is still an issue, considering people must leave behind family and other children.

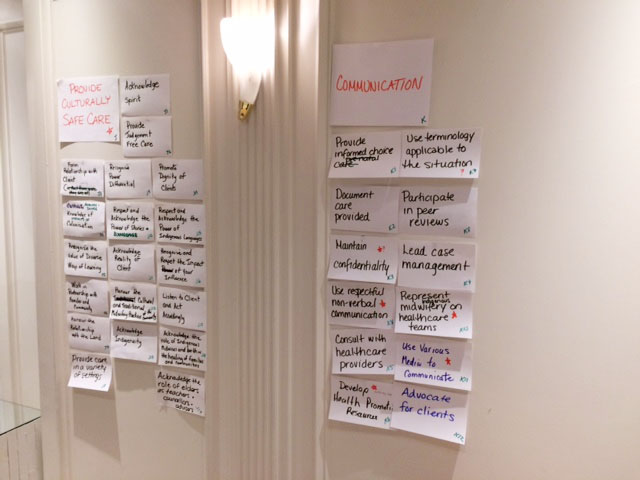

When I graduate, I hope to join and support midwives who are working hard to provide culturally appropriate care for Indigenous families, especially in remote northern communities. I strongly encourage other students to consider a remote community placement on their journey to becoming a midwife. Even though I did not attend any births, working in Attawapiskat only solidified my desire to work in Cree communities, and allowed me to practice clinical skills and understand a remote midwife’s scope of practice. In obstetrical emergencies, they are it!

Some day, I hope to see more midwives working in Cree communities and continuing to support all of the work that Christine Roy started many moons ago. I also hope to see and contribute to a Cree community-based Midwifery Education Program that would allow community members to become midwives without leaving the James Bay.

I had been looking forward to my third year in the Midwifery Education Program because of the potential opportunity to fly to my family’s ancestral lands and support my People as a student midwife. Now I look forward to graduating, life‑long learning, and solidifying clinical skills, which will make me a better health care provider to my People in remote northern Ontario.

Meegwetch